Black box testing is one of the most commonly used approaches in web application Vulnerability Assessment and Penetration Testing (VAPT). However, in practice, the definition of black box testing is often misunderstood, inconsistently applied, or overly simplified based on textbook explanations.

Traditionally, black box testing is defined as a testing methodology where no internal knowledge of the application is provided, and the tester interacts with the system purely from an external attacker’s perspective. While this definition is technically correct, modern applications and real-world testing engagements demand a more nuanced interpretation.

This blog aims to redefine black box web application VAPT by bridging the gap between textbook definitions and practical, industry-grade testing methodologies.

What Black Box Testing Really Means in Practice

From books and academic texts, black box testing is often described as:"Testing an application without any prior knowledge of its internal architecture, source code, credentials, or business logic — only the application URL is provided.“

This definition still holds true, but it needs important clarifications in real-world engagements. An application remains in black box scope even if:

- The client provides only the application URL

- The application has:

- A signup / self-registration flow

- A publicly accessible login page

- The tester can:

- Create their own account using public registration

- Access basic user-level functionality

As long as the following are not provided, the scope remains black box:

- No walkthrough of the application

- No explanation of business logic or workflows

- No documentation of user roles and permissions

- No credentials for privileged or non-self-registrable roles

- No internal APIs, architecture diagrams, or source code

- No clarification on sensitive business use cases

Only when additional role details, non-public credentials, business workflows, or explicit internal context are shared does the scope move toward grey box or white box testing. This distinction is critical for both testers and stakeholders to set the right expectations.

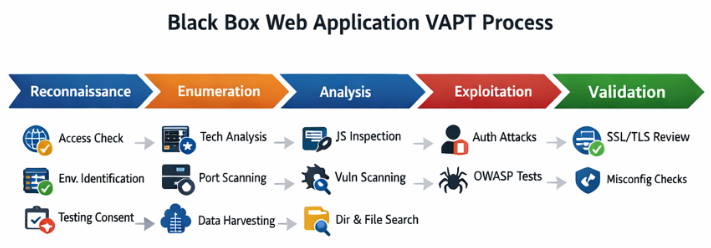

A Modern, Practical Black Box Web Application VAPT Methodology

Below is a structured, real-world black box testing approach that aligns with how mature VAPT teams operate today.

1. Application Accessibility Check

The very first step in a black box assessment is to validate whether the application is accessible at all. This involves opening the provided URL and determining whether the application is publicly reachable or restricted. Some applications may be accessible only via IP whitelisting, internal networks, VPNs, or specific geolocations. This step helps define whether the testing perspective is external or internal and sets the baseline for the attacker model being simulated.

2. Application Environment Identification

Once accessibility is confirmed, the next step is to identify the environment in which the application is deployed. Applications may run in production, staging, UAT, or development environments, and each carries different risk implications. Environment details can often be inferred from response headers, subdomains, error messages, banners, or exposed debug information. Non-production environments frequently have weaker security controls and are often overlooked.

3. Authorization and Consent for Testing

Before performing any active or intrusive testing, it is critical to obtain explicit authorization from the client or application owner. This includes clarity on whether both passive and active scans are permitted and whether testing can be performed during business hours. This step ensures legal compliance and avoids unintended service disruptions, especially in production environments.

4. Technology Stack and WAF Enumeration

Understanding the technology stack is essential for tailoring attack techniques. Tools such as Wappalyzer and Nmap can help identify backend frameworks, programming languages, web servers, databases, and third-party integrations. At this stage, it is also important to determine whether the application is protected by a Web Application Firewall (WAF), as this influences payload selection and testing strategies.

5. Open Ports, Services, and Transport Layer Review

Black box testing should not be limited to HTTP endpoints alone. Identifying open ports and exposed services helps uncover unnecessary or misconfigured services. This step also includes checking whether the application is accessible directly via its origin IP, potentially bypassing WAF protections, and verifying whether the application allows unencrypted HTTP communication instead of enforcing HTTPS. It also can help in identifying API Documentation Pages, Admin Panels etc exposed over a different port.

6. Vulnerable Libraries and Plugin Identification

Modern web applications rely heavily on third-party libraries and plugins. Tools like Retire.js can be used to identify outdated or vulnerable JavaScript libraries in use. Vulnerable dependencies often lead to client-side issues such as cross-site scripting, prototype pollution, or logic flaws, making this an important step even in black box scenarios.

7. Google Dorking for Public Exposure

Although you wont find this in most of the VAPT methodology or steps, Google Dorking is an effective OSINT technique to identify publicly exposed information indexed by search engines. This may include documents such as PDFs, Excel files, backup files, or unintended endpoints. Such findings can result in sensitive information disclosure without directly interacting with the application itself.

8. GitHub Dorking for Source Code and Credential Leaks

Similar to Google Dorking, this will also be not there in many traditional VAPT approaches/ methodologies, However Public GitHub repositories often contain accidentally exposed credentials, API keys, tokens, or even application source code. Searching GitHub using targeted dorks allows testers to identify leaks that may lead to direct compromise. This step closely mimics real-world attacker behavior and often yields high-impact results.

9. Web Archive Enumeration

Historical versions of an application can reveal forgotten or deprecated functionality. By analyzing data from the Wayback Machine and CLI tools such as gau and waybackurls, testers can uncover old endpoints, admin panels, or APIs that may still be accessible but no longer linked from the live application.

10. JavaScript File Collection and Analysis

JavaScript files represent one of the richest sources of intelligence in black box testing. Files collected from archives, spiders like Katana, dorks, and application sources should be analyzed to identify hidden parameters, API endpoints, internal paths, post-login functionality, and hardcoded secrets. This analysis can be performed manually or automated using dedicated tools and scripts.

11. Hidden Parameter Discovery

Applications often process parameters that are not visible in the UI. Tools like Arjun or Param Miner extension from burpsuite help identify such hidden or undocumented parameters, significantly expanding the attack surface for injection-based vulnerabilities. This step is particularly valuable for API-heavy and legacy applications.

12. Directory and File Enumeration

Directory scanning remains a fundamental activity in black box testing. Scans should be performed not only against the base URL but also against paths identified from JavaScript files and web archives. Tools like dirsearch, dirbuster, ffuf etc can be used to perform directory bruteforcing. Recursive scanning helps uncover hidden directories, backup files, administrative panels, and configuration files that are not meant to be publicly accessible. Wordlist from popular github repo like SecLists can be used.

13. Network and SSL/TLS Assessment

Using tools like Nmap, testers can identify additional open ports and services that may not be immediately obvious. SSL and TLS configurations should also be reviewed to detect weak ciphers, deprecated protocols, or certificate-related issues that can weaken transport-layer security.

14. Automated Vulnerability Scanning

Automated scanners such as OWASP ZAP, Burp Suite, Nikto, Nessus etc play a supporting role in black box VAPT. These tools help identify common misconfigurations such as missing security headers, directory listing, private IP disclosure, and information leakage. However, their findings should always be validated manually.

15. Broken Link and External Reference Analysis

Applications often reference external resources such as social media pages or third-party services. Identifying broken or abandoned links can expose opportunities for broken link hijacking, which attackers may exploit for phishing, brand impersonation, or reputation damage.

16. CDN and Cloud Storage Misconfiguration Review

Many applications integrate with CDNs and cloud storage services such as AWS S3, Azure Blob Storage, or Google Cloud Storage. References to these services can often be found in JavaScript files or network traffic. Misconfigured storage buckets may allow unauthorized access to sensitive data.

17. Authentication Attack Surface Testing

Authentication mechanisms must be thoroughly tested for weaknesses such as default credentials, user enumeration, brute-force vulnerabilities, authentication bypasses, and logic flaws. Techniques inspired by real-world attack scenarios and PortSwigger labs provide valuable guidance during this phase.

18. OWASP Top 10 Coverage

A comprehensive black box assessment must include systematic testing for vulnerabilities outlined in the OWASP Top 10. This ensures coverage of the most critical and commonly exploited security risks across modern web applications.

19. Authorization Testing Across APIs and Endpoints

Finally, all identified endpoints, especially APIs discovered during JavaScript analysis, should be tested for authorization flaws. This includes checking for IDORs, broken object-level authorization, and broken function-level authorization. Authorization issues often result in high-impact findings in black box assessments.

20. WAF Origin IP Identification and Bypass Attempts

In modern web architectures, applications are frequently protected behind Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) or CDNs such as Cloudflare, Akamai, Fastly, or Imperva. While these controls provide an additional security layer, they also introduce a critical testing consideration during black-box VAPT, whether the WAF is the only exposed surface, or if the origin infrastructure is unintentionally reachable. If an origin IP is identified, controlled validation attempts should be performed to confirm whether the application responds outside the WAF protection. A mature black-box assessment should include attempts to identify the origin server IP behind the WAF.

Black box testing is not a shallow or limited assessment. When performed correctly, it provides a realistic attacker’s view of an application and often uncovers critical issues that grey box or white box testing may overlook. By redefining black box VAPT to reflect modern application architectures, tooling, and attack techniques, organizations can gain far more value from their assessments—without compromising scope clarity or engagement expectations.

A well-executed black box test is not about what the tester is given, but about how effectively they can think and operate as a real attacker.

Very knowledgeable blog for real world Black Box Testing.